The Pillar Dollar Wreck (BISC0035)

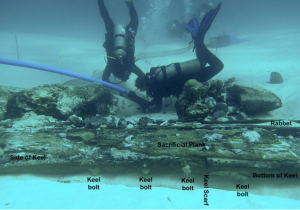

Located within Biscayne National Park (BNP), Florida, this site is believed to be a Spanish shipwreck from the eighteenth century. It was first located in the 1960s and has been extensively looted since. In September 2014, I ran an advanced maritime archaeology field school at the site. We conducted survey, excavation, and mapping of the site under Permit BISC 2014-001. In 2016, a second excavation season was conducted at the site, under permit BISC 2016-001, during which large-scale excavation of the entire hull structure was undertaken to recover and record the complete site using manual techniques and photogrammetry. Ongoing research will help to identify the shipwreck’s cultural affiliation and lead to more interesting conclusions about Spanish shipping in the Florida Straits during the eighteenth century. It will also help the park interpret a shipwreck that was largely written off because it was so heavily looted.

Three ECU Master’s theses have been completed as a result of this project. Melissa Price explored how the site has been impacted by looting and treasure hunting and how that compares to other colonial period sites in the Florida Straits (Price 2015). Annie Wright investigated the use of photogrammetry and the production of 3D models via 3D printing for public interpretation (Wright 2018). Madeline Roth analyzed the 2016 field project to determine the site’s significance and to provide park staff with resources for public interpretation (Roth 2018).

For more information about the Pillar Dollar Wreck check out the report.

The Spanish Landing Site

Inland waterways are an important part of the maritime cultural landscape and seascape and were vital to Spanish exploration, colonization, trade, and movement during the Spanish colonial period in Florida. Unfortunately, little research has focused specifically on these waterways. The Spanish Landing site (8WA247) in Wakulla County provides one example of inland waterway use in the Apalachee Mission area of northwest Florida. Although the site has been looted since at least the 1960s, State underwater archaeologists have recorded the underwater portion of the site, as well as conducted a brief terrestrial survey and shovel tests in the area. In 1989, the State found two river divers suspected of impacting the site and collecting artifacts, which were then assumed by the State for documentation and preservation, but no thorough analysis of the material was completed. In 2001, I conducted additional fieldwork at the site including side-scan sonar survey and a non-disturbance visual and pedestrian survey of the extant underwater and upland areas of the site. I also conducted artifact analysis on the State’s collection of 2,418 artifacts from the site.

For more information about the site and research, see this publication and my thesis.

1733 Spanish Galleon Trail

Compared to the earlier 1715 Spanish fleet disaster on the east coast of Florida, little “treasure” has been recovered by treasure hunters from the 1733 wrecks, largely due to Spain successfully salvaging the shipwrecks immediately after the disaster. Regardless of the lack of “treasure,” people continue to loot the 1733 shipwrecks in search of non-existent gold, silver, precious stones, and jewels. As a result, the historical and archaeological values of the shipwrecks have suffered, which then make it difficult to preserve and interpret these shipwrecks. Florida’s Bureau of Archaeological Research partnered with the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS), John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park, and Biscayne National Park to conduct a one-year project to inspect and document the 1733 Spanish Plate Fleet shipwrecks and to create a “Spanish Galleon Trail” by which visitors may tour “real life” Spanish shipwrecks and learn their true stories. This project was funded in part by a research grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) through the Florida Coastal Management Program.

During the summer 2004 season, a crew of four archaeologists from the Bureau relocated and surveyed each of the thirteen sites, and connected with local researchers and managers concerned with these shipwrecks. Using data sheets, we ranked the sites according to their archaeological integrity and opportunities for visitation as part of the 1733 Spanish Galleon Trail. We released the information through an interpretive guide book and an informative website with the goals of sharing the true story of the 1733 fleet, promoting a sense of pride and ownership in the Florida Keys’ unique maritime heritage, and encouraging visitors to become involved in the preservation and the promotion of heritage tourism. Master’s student Olivia Thomas examined artifacts associated with Spanish colonial “foodways” from the 1715 and 1733 Spanish fleets for her thesis (Thomas 2017). To read more about the trail, read this article.

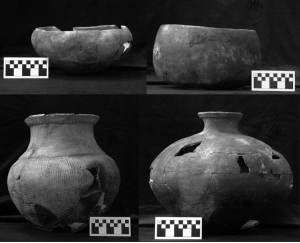

Tonalá Bruñida / Guadalajara Polychrome

Tonalá Bruñida is an Indigenous Mexican ceramic that has remained in production since the colonial period to today. It is known from historical documents that it was coveted and consumed in high volumes as a luxury commodity among the upper socioeconomic classes of Spain, particularly by women. In fact, this ware was shipped whole and in bags of broken sherds from Mexico to Saipan and is found in great quantities on 18th century shipwrecks throughout the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. Using a combination of ethnographic and chemical analyses, the project aims to investigate the nutritional and cultural values associated with this intersection of material culture and geophagic (i.e. eating soil or clay) practices.

I’m currently working with a MA student on this project which involves ethnographic research in the Guadalajara region and the examination of ceramics from terrestrial and 18th century shipwrecks. The project also consists of applying Pxrf and SEM analyses to investigate the composition of sherds. We gave a paper at the recent Society for Historical Archaeology Conference (2025) with the abstract here:

Búcarofagia: Preliminary Investigations on the Consumption of Tonalá Bruñida Ware by Dorian Record and Jennifer McKinnon

Tonalá Bruñida is an Indigenous Mexican ceramic ware that originated in the late colonial period and is still in production today. This ware is distinguished by its paste, made from a combination of two clays native to the Tonalá region, by a distinct slip which produces a specific scent when in contact with water, and by a meticulous process of burnishing. Tonalá Bruñida was eaten and consumed in high volumes as a luxury commodity among the elite classes of Spain. In fact, it grew to such significance that it was shipped in great quantities whole and in sherds for distribution among the upper classes across Europe, as evidenced by its extensive presence on multiple shipwrecks of the period. This paper presents preliminary results of a project investigating the nutritional and cultural values associated with the geophagia and cultural commodification that inspired the extensive maritime export of an Indigenous ceramic product.