Corcovado National Park is a large tract of lowland rainforest on a peninsula next to Golfo Dulce in southwestern Costa Rica on the Pacific Coast (Corcovado). In 1989, while I had originally planned to work in Panama, the increasing chaos associated with the upcoming election eventually led the STRI administration to advise US citizens not to come to Panama if they were not already there. Some readers may recall from that time that there was extreme conflict between Manuel Noriega and the U.S., and between Noriega’s political party and the opposition. In fact, shortly before I was to leave for Panama, Time magazine published a cover photo of Guillermo Ford (the vice presidential candidate for the opposition) covered with blood (which was from his body guard, who was killed in the conflict), being beaten with an iron bar by some of Noriega’s thugs (iconic photo). Eventually things came to a boil and President Bush ordered the invasion of Panama by US armed forces, but in the months leading up to the invasion tensions rose and it became very difficult for researchers to get in (or out). So my assistant and I went to Costa Rica instead. I decided to work in Corcovado because it has a high diversity of poison frogs, including Phyllobates vittatus, Colostethus talamancae and C. nubicola, and Oophaga granulifera. Working there was a tropical biologist’s dream – the diversity of life was incredible (the National Geographic Society has called Corcovado “the most biologically intense place on earth”). One of the most impressive things about Corcovado is the density of large animals, such as jaguars, tapirs and white-lipped peccaries.

It is a cliché in ecology that it is rare to see instances of predation in the wild. It is also a cliché that it is rare to see top predators in the wild, such as jaguars and harpy eagles, although glimpses of such “charismatic megafauna” are highly sought after. Nevertheless, researchers do occasionally see instances of predation in the field, and once in awhile we are fortunate enough to see big predators “up close and personal”. My own experiences with predation and big predators have mainly happened in Corcovado. Although I have worked in many other remote rainforest locations, Corcovado seems to have an abundance of predators for reasons that are not clear to me. It may be that the park (which is protected from poaching to some extent) contains an abundance of predators that spend at least part of their lives within the park boundaries to avoid humans that are encroaching on the forested areas that surround the park, but that is pure speculation.

One of the oddest examples of predation that I have observed involved a sloth. I was standing at the base of a large tree off a lowland forest trail in Corcovado one afternoon when I heard a loud “WHUMP!” and felt the impact of a large object landing on the ground right next to me. I turned to see a large sloth lying on the ground at my feet. Upon closer inspection, I found that the sloth (which was quite dead) had horrific wounds on its head. It’s eyes had been plucked out, and it’s braincase had been pecked open, apparently by a large bird. How had this mortally wounded sloth, obviously a victim of a predation attempt, come to fall out of a tree and land right next to me? I have puzzled over this ever since, but two possibilities seem most likely. One, the sloth may have been killed by a large bird of prey (e.g. a harpy eagle), and carried to a high branch (not uncommon:Harpy hunting sloth; Harpy eagle with sloth). The harpy eagle could have released the prey momentarily on the branch to do something else, whereupon the sloth could have slipped off the branch, landing next to me at the bottom of the tree. Alternatively, the sloth may have originally been in the tree and been attacked by a large bird of prey. It might have continued to hang on to the tree even after receiving mortal wounds from the Harpy. If the eagle eventually gave up and flew away, the sloth might have gradually released its grip as it relaxed in death, ultimately falling at my feet long after its killer had left the scene. In any case, I did not see the actual bird of prey, so this is quite speculative.

Harpy eagles are one of the most magnificent birds of prey in the world (Harpy Eagle), and I still have not seen one in the wild. An acquaintance of mine in Panama, Dr. Alberto Palleroni, was working on a project raising wild Harpy Eagles in Soberania National Park, and I was fortunate to see him give a lecture in which his main prop was an actual harpy eagle that sat on the podium during the lecture! The amazing bird was completely calm during the entire lecture, looking at the audience with absolutely no fear whatsoever. Given that primates make up a large part of the harpy eagle diet, a roomful of potential prey was probably of more culinary interest to the harpy than anything else. Fortunately Dr. Palleroni had thought to provide the eagle with a sloth arm before the lecture, which he held in one talon and thoughtfully pecked at from time to time during the lecture. This bird was the male of a pair that were later released on Barro Colorado Island (BCI). This release had fascinating effects on the behavior of the primates on the island, who had not been exposed to aerial predators since the formation of the island in 1913 (Harpy eagle study). The eagles are impressive predators, and in fact one researcher witnessed one of the eagles swooping down and carrying off two young peccaries at one time, one in each talon! Unfortunately the experiment ultimately came to a bad end, as the male flew off the island and was shot by a rancher concerned that the large bird would attack his livestock.

During the four months that I did research in the field in Corcovado, I wanted very much to see a jaguar, as I have always been fascinated by the beauty and power of the big cats. Jaguars are known to be particularly abundant in Corcovado, although it is not always easy to see them. For example, Dr. Lawrence Gilbert, who had worked in Corcovado for many years when I worked there in 1989, had never seen a jaguar. One of his students wanted to see a jaguar so badly that he carried out what most would consider a rather foolish experiment. For awhile some of the park staff attempted to breed horses at the Sirena field station, but this ultimately proved futile because any foal born would soon fall victim to jaguar predation. Sometimes the jaguar would kill and consume some of the foal, then leave it to return and feed on it again the next night. After a foal was killed in this manner, Dr. Gilbert’s student tied a long rope from the carcass of the foal to his own ankle, where he slept on the porch of the field station, clutching his camera to his chest. At about three in the morning, the student was rudely awakened by being dragged off the porch, as a jaguar dragged the corpse of the foal toward the forest. He had the presence of mind to take a picture of the jaguar, which I saw years later. It shows the baleful stare of what appeared to be a very perplexed jaguar. On the other hand, some researchers had a much easier time seeing Jaguars in Corcovado. For example, a primatologist working on squirrel monkeys there had a jaguar approach her in the forest and start playing with her backpack (on the ground) like it was a cat toy! Sometimes jaguars just seem to be in a playful mood (Playful jaguar in Peru)!

Despite working in Corcovado for three months solid, and frequently going out at night, I did not see a jaguar during that field season. I even tried hanging out meat to attract the big cats to my field site. This actually worked, but it attracted a jaguarundi, rather than a jaguar. These are relatively small cats, with long bodies, rather short legs, and curiously small heads. As I was sitting on a stump writing notes one afternoon, a jaguarundi came running directly toward the hanging meat. After running almost over my feet, the cat glanced in my direction, apparently noticing me for the first time, and then simply kept on running, past me, past the meat, and into the forest.

It was not until I returned years later to visit Corcovado once again, that I was finally able to see jaguars. My companion, Ruth Hamilton, and I hiked to Sirena, and then decided to cross the Sirena river and head north to the station (more of a campsite really) called La Llorona. Crossing the river was always exciting, given the frequent predator traffic. The river emptied into the Pacific ocean at Sirena, and large bull sharks regularly swam up into the river to hunt in the brackish water where the river meets the ocean (Sharks in the river). Meanwhile, large crocodiles from the river liked to swim in the opposite direction, presumably to try seafood for a change (Costa Rican river crocs: these crocs are from a different river, but you get the idea…). These crocs are not averse to human flesh if it is available (croc attacks surfer). Wading through the water at low tide around midnight gave one a keen sense of excitement, to say the least.

Having reached the north side of the river, we headed up the beach toward La Llorona. After hiking for about an hour, we came upon a large jaguar on the beach, but it was not alone. In fact, it was perched atop a huge sea turtle. It had made a basketball-sized hole directly through the middle of the turtle’s shell, and was busy scooping out the turtles internal organs when we arrived (Jaguar vs. Sea Turtle). Upon seeing us, the jaguar ran off into the nearby forest, no doubt waiting for us to leave so it could return to its feast. The turtle was beyond helping, and we left it to its gory fate. Reflecting on the jaw strength of an animal that could bite through the thickest part of a sea turtle’s shell gave us a new appreciation of the power of these big cats. In fact, there are few animals that are too big to be on the jaguar’s menu, including large caiman (Jaguar hunting caiman).

After several more hours of hiking we arrived at La Llorona for a beautiful dawn. We spent a lovely day there, and decided to have a quiet Kai Pirihna on the beach while watching the sunset. As we sat together looking out to sea with our drinks, I had the curious sensation of being watched. Turning to look back toward the forest, we saw, not fifteen feet away, a beautiful young jaguar, watching us with calm interest and curiosity. For what seemed like an eternity but was probably only a few seconds, we all remained perfectly still, except for the end of the jaguar’s tail, which twitched back and forth, back and forth. Finally the jaguar turned and disappeared into the forest, as silently as it had arrived. We hiked back to Sirena that night, and once again encountered another jaguar on the beach as we hiked along. This one did not seem perturbed by our approach, and let us come very close before finally loping off into the forest. So, after months of working in Corcovado and not seeing a jaguar, we saw three in three days! Jaguars are apparently quite fond of the beach – this makes sense as the large tides of the Pacific ocean in Costa Rica produce extensive tide pools that contain a seafood smorgasbord for hungry big cats (including the occasional sea turtle)!

Another of the jaguar’s favorite foods in Corcovado is the peccary. Actually, there are two kinds of peccaries in Corcovado, the collared and the white-lipped peccary. Collared peccaries are somewhat small, whereas white-lipped peccaries are actually quite large, and travel in large herds. Despite being featured on the jaguar’s menu, peccaries can be quite tough and aggressive, and can actually give inexperienced jaguars a run for their money (jaguar vs. peccary). There are many stories of people being chased up trees by angry peccaries. In Corcovado, it was not uncommon to see large herds of white-lipped peccaries (and one could often smell them before seeing them – they have a very potent odor!). One day, I had to hike for several hours from Sirena to La Leona at the southern border of the park in order to catch a bus to Golfito. The bus left very early in the morning, so I had to start my hike at about 2 am to make it on time. As I was hiking along at around 5 in the morning I heard (and smelled) a large herd of peccaries on the trail a hundred meters or so ahead of me. I didn’t want to blunder into a herd of peccaries in the dark (a risky proposition), but on the other hand, I didn’t want to miss my bus. Eventually I decided I would make alot of noise, in the hope that this would scare the herd away. After yelling and snapping some branches and jumping up and down for several minutes, I heard squeals of fright and the frantic trampling of many hooves into the forest. After a few minutes, all became quiet, and I assumed that the peccaries had fled. I resumed my walk along the trail. Dawn was just approaching and as I walked through the forest the light started to filter through the branches. As I walked through the area where the peccaries had been foraging, I suddenly realized that I had entered a gauntlet – all of the male peccaries from the herd had lined-up on either side of the trail. As I walked through the gauntlet, they began to loudly clack their long, sharp teeth (white-lipped peccary; clacking peccaries). As I walked by each pair of males (one on each side of the trail), they moved onto the trail and followed me, clacking all the while, until I had a demonic entourage of twenty or so male peccaries, all clacking like crazy. There was nothing for it but to just keep on walking – if they wanted to tear me to pieces there was nothing I could do about it. Fortunately for me, they were not in the mood to attack, but merely escorted me away from the area, returning (I assume) to forage with the females and little ones as soon as I reached what they considered to be a safe distance.

Another exciting group of animals in Corcovado are the pit vipers, particularly the fer-de-lance (Bothrops asper). This species is incredibly common in the Corcovado rainforest. I have never seen such a high density of pit vipers in any forest. And these beautiful snakes can be dangerous – in fact a famous ecologist was bitten by a fer-de-lance in the park while walking along an arroyo (the snake was coiled high up on the bank and bit him in the arm). Despite working in a number of arroyos (and seeing many vipers), we were lucky and did not receive any bites (or even strikes). I was not so lucky years later, when I was bitten by a fer-de-lance, in (of all places!) a parking lot in Gamboa, Panama. My assistants and I had parked in a parking lot in front of an apartment run by the Smithsonian. Unpacking the car, I apparently put a cooler down on top of a young fer-de-lance without even realizing it (or the snake may have slithered under the cooler after it was put down). When one of my assistants came and picked up the cooler, the snake (which as agitated at this point) struck and bit me on the foot, right through my sneakers. I immediately killed the snake (to make a positive ID), and contacted Stan Rand, a STRI staff scientist and my advisor. He notified the US Army hospital in Balboa, and they brought me to the hospital, where they took blood every hour through the night to see if there was any venom circulating in my blood. Fortunately, despite the two neat holes in the heel of my foot, I never experienced any of the classic symptoms of a pit viper bite, such as swelling, redness and extreme pain. Apparently this had been a “dry bite” – sometimes pit vipers will deliver a bite without injecting any venom – whether as a (low cost) warning, or simply because they haven’t had time to move enough venom into position for injection is not clear. Whatever the reason, I was very grateful not to have received a dose of the venom of this species, which is hemolytic and also extremely destructive to muscle tissue (it rapidly digests proteins).

Coral snakes were also fairly abundant in Corcovado. These beautiful snakes serve as the models for a number of non-toxic mimic species. Little did I know it at the time, but years later I would make mimicry one of my main areas of study. Not in snakes, however, but in poison frogs (see Tarapoto page). Research on coral snake mimicry has been extensive in the Northern hemisphere, but the tropical species are less-well studied. Nevertheless, tropical coral snakes have been the subject of some classic studies in evolutionary herpetology.

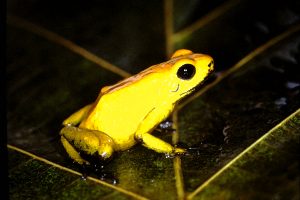

My research in Corcovado focused on four species of frogs, Phyllobates vittatus, Oophaga

granulifera, Colostethus talamancae and C. nubicola. Observations on the behavior of these species made for a nice comparison with my previous work on other species of poison frogs. Phyllobates vittatus, C. talamancae, and C. nubicola all have male parental care, but the latter two are non-toxic, whereas P. vittatus is highly toxic, with the most toxic alkaloid known (batrachotoxin) in its skin (albeit in small quantities). Phyllobates vittatus has a big cousin in the Choco region of Colombia, Phyllobates terribilis, which is the most toxic frog on earth(!). It has batrachotoxin, an incredibly toxic alkaloid, in its skin (poison frogs). In a bizarre twist, this same toxin is also found in poisonous birds in New Guinea! (Poisonous Pitohui). The frogs and the birds are thought to get the toxin from choresine beetles in their diet (Pitohui article). The Embera tribe, who live in the Choco, have long used this species to make poison darts for their blowguns, which they use to hunt for monkeys (Poison dart frogs). My friend, Mark Moffett, a National Geographic photographer at the time, tells a fascinating story of photographing these frogs and the process of poison dart manufacture in this video (Mark Moffett: finding Phyllobates).

Although P. vittatus has only tiny amounts of batrachotoxin in its skin, it is still highly potent. I foolishly handled a frog with no gloves on one day, without realizing that I had a small lesion on one finger. Afterward, the cut started to throb with pain. Instead of subsiding, the pain began to move up my wrist and then my arm (over several days), and coincidentally I started to feel very sick: dizzy, nauseous and lethargic. After a few days of this I begged a ride with a couple of tourists on a single engine plane back to San Jose (the capital city in Costa Rica) and went to a medical clinic for tests. They told me they did not find any evidence of poison in my system, but that I did have amoebic dysentery. I think doctors at the clinic were quite surprised when I let out a sigh of relief after learning that my symptoms were caused by amoebic dysentery!

Summers, K. 2000 Mating and aggressive behaviour in dendrobatid frogs from Corcovado National Park, Costa Rica: a comparative study. Behaviour 137: 7-24 (BehaviourCorcovado).