I went to Venezuela for the first time in 1987, to study the yellow-banded poison frog, Dendrobates leucomelas. This species has male parental care, and I wanted to compare its patterns of care and mating strategies to those of Dendrobates auratus (also with male parental care), which I had been studying in Panama for several years. I contacted a herpetologist by the name of Steve Gorzula, an englishman who lived in Guri, in eastern Venezuela. He worked as a survey biologist for EDELCA, the Venezuelan electric company, doing faunal surveys of regions impacted by EDELCA’s development projects, such as the Tepuis (table-top mountains). Steve met me on my way to Guri, and immediately offered me a place to stay during my entire time doing research (over 3 months). He was always supportive and helpful – I was very lucky to have found him. He also had great stories from his many years in the field.

Guri was a strange town. Built by a North American company to accommodate American workers constructing the Guri dam, the town had a distinctly North American feel, yet was out in the middle of nowhere in the dry-forested hills of eastern Venezuela. The houses were very nice and modern, and the supermarkets were well-stocked with foods from the states that you would never expect to see in a remote part of South America.

I rode a bike to the field everyday, and was able to find an excellent field site to study D. leucomelas. The site was in dry forest, but during the rainy season the frogs were quite active and I had no trouble finding frogs to observe and study. This species turned out to have a mating and parental system that was very similar to that of D. auratus, which was not surprising but was gratifying. I was ultimately able to compare both of these species to Oophaga sylvatica (called Dendrobates histrionicus at that time), a species with female care in Ecuador. This comparison became the third chapter in my PhD thesis, and was published in 1992 (CompMatingStrats-Dendros).

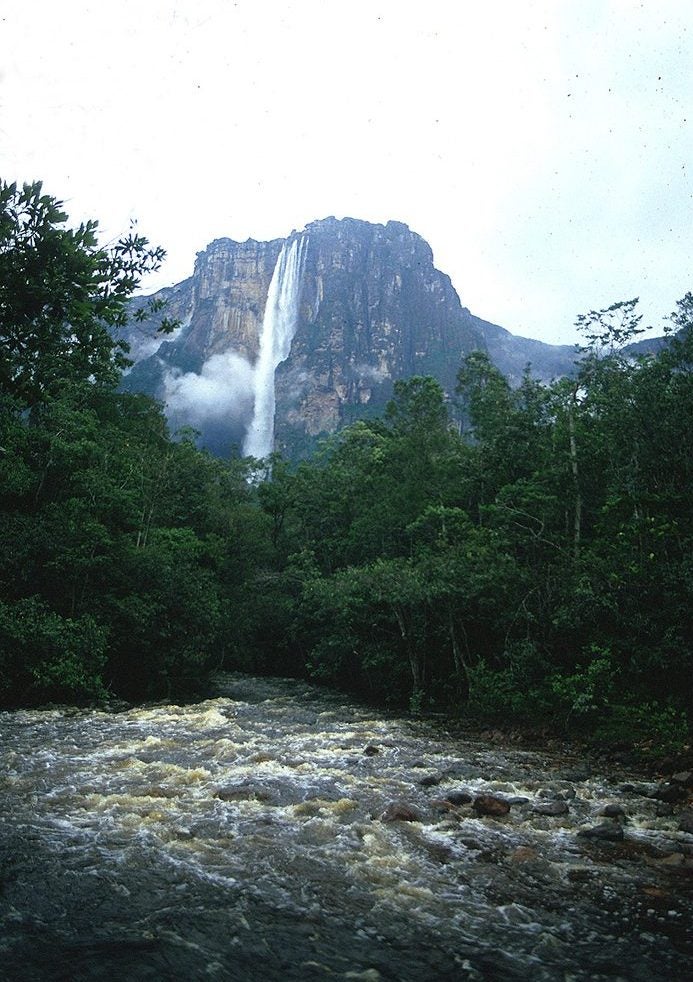

While in Venezuela I also traveled to Auyantepui in the Guyana Highlands, home of the famous Angel Falls, the highest waterfall in the world. The Tepuis (“Home of the Gods”, in local Pemon tribe mythology) are ancient formations of pre-cambrian quartz sandstone. The isolated table-top mountains were formed by erosion of the Guyana Shield in the ancient past, and over vast spans of time they have become highly isolated from each other – truly “Islands in the Sky”.

I must say this region is one of the most beautiful places I have ever been, with absolutely spectacular scenery.

With regard to research on D. leucomelas, Canaima turned out not to be the best field site, as the frogs were not as active in terms of breeding as they were in Guri. Nevertheless, my time in Canaima was interesting, and from a biological perspective the Tepuis are a fascinating phenomenon. Ever since Arthur Conan Doyle had written about the “Lost World”, people have been fascinated by the idea of prehistoric beasts (e.g. dinosaurs in Conan Doyles book) roaming the tops of these table-top mountains, relicts of the ancient past isolated on these “sky islands”. Although the Tepuis turned out not to be dinosaur havens, there are a variety of unusual endemic fauna and flora found on them, apparently adapted to the inhospitable (cold, wet, low nutrient) environment characteristic of these table-top mountains. This is true for frogs, and one can find bizarre-looking species such as members of the genus Oreophrynella (Oreophrynella Wiki). How these Tepui endemics evolved has been the subject of much interest and debate in the scientific community (Stefania evolution) (Oreophrynella evolution)

I returned to Venezuela many years later in order to collect tissues for some phylogenetic analyses of Dendrobatid frogs that I was engaged in at the time. This trip took me to Puerto Ayacucho, in the southern part of Venezuela. The color pattern morph of D. leucomelas I found there was very beautiful, as you can see from a photo of this frog on the left.

The region of Southern Venezuela near Puerto Ayacucho is covered with dense rainforest, but the climate is somewhat cooler than other regions. There are tepuis in this region, but they are more spread out, among vast tracks of rainforest. The substrate is very rocky, with numerous waterfalls and waterslides, as seen in the picture below.

During my time in this region, we passed through the outskirts of the territory of the Yanomamo tribe. This tribe is famous in anthropological circles, particularly for the work of Napoleon Chagnon, who lived with and studied the Yanomamo for decades. I had heard about Dr. Chagnon’s work for many years before I visited the region – one of my major professors at the University of Michigan (Richard Alexander) was close friends with Dr. Chagnon, and he would frequently refer to research on the Yanomamo in his “Human Behavior and Evolution” course. I remember being astounded the first time I saw the film “The Axe Fight”, which revealed the complex politics of intra-village violence and group fission (The Axe Fight). “Indiana Jones” has nothing on Dr. Chagnon – his years among the Yanomamo included a number of near death experiences. Dr. Chagnon has become a controversial figure (New York Times article), having been accused of exaggerating (or causing) the violence he documented, and even of participating in genocide (as part of a vaccination project against measles(!)). My own interpretation is that Dr. Chagnon was a dedicated observer who did his best to objectively document the social and political lives of the Yanomamo, giving insight into many facets of human nature in the process. Of course, Dr. Chagnon is quite capable of defending himself – I highly recommend his book: “Noble Savages: My life with Two Dangerous Tribes: the Yanomamo and the Anthropologists”(!).