Limoncocha is a small Quechua village established by missionaries on a lake (cocha) near the Napo River in Amazonian Ecuador. It lies in an area that has been the focus of conflict, as it is one of the most biodiverse areas on earth, and home to indigenous people (the Waorani and related tribes), yet also sits on top of huge oil reserves that corporate and governmental entities are eager to develop and exploit (Yasuni). I first visited Limoncocha in 1988, but only for a short time. I then returned as a National Science Foundation NATO postdoc on a National Geographic grant in 1993, to study the reproductive behavior of Dendrobates ventrimaculatus (now Ranitomeya variabilis).

This was just when a massive oil pipeline was being extended into this Amazonian region, and it was packed with oil workers. In order to work in the area, one had to get permission from the oil company (Maxus at the time), which involved a trip to a nearby administration center. My assistant, Kate Holmes, and I went to the center and were told to watch a video. The video showed pictures groups of Waorani walking on trails in the forest and the voice-over said: “If you are walking in the forest and meet a group of Waorani natives, make sure you do not stare at the women in the group”(!) Further, the voice-over continued “If you are walking along a trail in the forest and you see a basket hanging upside down, turn and walk quickly back the way you came.”, and then “If you are walking along a trail in the forest and you see two spears crossed over the trail, turn and run away immediately”(!) The oil company had apparently lost a number of workers due to misunderstandings during encounters with the Waorani. This was not new. In fact the region had become famous in the 1950’s when a group of missionaries tried to make contact with the Waorani and were killed with the large spears that were one of the trademarks of this tribe (Operation Auca). This was widely publicized and actually detailed in several films (e.g. “The End of the Spear”). Later, missionaries infiltrated the area and set up several missions. Some missionaries even went out into the forest to live with groups deep in the forest, although this sometimes ended badly (one such missionary was found pinned to the ground by about twenty ten-foot long wooden spears). The adoption of sedentary life by some Waorani (and related tribal groups) led to a split in the tribe, with some groups settling permanently at the missions, and others maintaining a more nomadic, traditional hunter-gatherer lifestyle. This site (Waorani History) provides an interesting and detailed account of Waorani history up until the early 2000s. Unfortunately, the influx of weaponry (especially shotguns) from “civilization” created severe disparities in firepower between some groups (i.e. those that did and did not have access to shotguns), and lead to some bloody confrontations (Waorani warfare).

The Quechua village where Kate and I stayed in Limoncocha was noisy, with trucks and oil workers passing through all the time, but was still quite beautiful, and close to fairly pristine forest. The Waorani lived across the wide Napo River, so there was no problem with us being considered intruders. The research on R. variabilis (on breeding behavior) went very well, although we did suffer from frequent stomach problems during our stay. This may have begun with an unwise decision – during a party held by our Quechua landlady, Carmela, we were offered, and accepted, bowls of “chica”, an alcoholic gruel (Chica) that is made by the village women, who chew and spit yucca (casava) into a large vat where it ferments in the tropical climate. Definitely not the most hygienic libation! We were sick for days after drinking it, and never really had normal digestion during our stay. Carmela was sympathetic and tried to help, but didn’t really know what to do for us.

One day, as we sat in her small restaurant, slumped over the table, she said “I know what you two need to fix you up!” She had just returned from a wedding, and had a large paper bag with her. She reached in and pulled out… a roasted howler monkey! Apparently monkey is a traditional wedding dish in this region. The poor monkey had all its fur burned off, and its face was twisted into a horrible grimace, as the flames had peeled the flesh back from its teeth. We both nearly lost what little food we had in out stomachs, and fled the dinning room, blurting an excuse about having to get back to the field right away.

Generally speaking, life in the village was quiet, but we did have a few exciting episodes. The word “cocha” refers to long lakes that form when a river changes course (a common phenomenon in Amazonia), and leaves behind a section of river, now cut off from the current path of flow. The lake was quite beautiful, and we would sometimes go out to the middle of the lake in a dugout canoe to go swimming. The locals said this was safe, although they said to stay away from the heavy aquatic vegetation that grew close to the shore, as this was the hangout of some dangerous wildlife, such as large electric eels, black caiman and giant anaconda. Black caiman are the largest caiman, and can reach 16 feet in length, although individuals this large have been hunted out in most places (Black Caiman). Electric eels can also be quite aggressive, and have even been known to kill caiman (Electric eel attacking; Electric eel and caiman). Anaconda are the heaviest snakes in the world, and they are highly aquatic. They also have an appetite for caiman (Anaconda vs. Caiman).

From time to time, we would go to the middle of the lake to go swimming. One day, on our way out to the middle of the lake, a huge storm blew up from out of nowhere. It was amazing how quickly the sky turned black and the storm clouds rolled over us. The wind became ferocious, blowing white caps on the normally calm surface of the lake, and the rain literally came down in buckets. We tried to paddle back to shore, but within a few minutes the cayuco (dugout canoe) was completely swamped and sank, leaving us treading water in the middle of the maelstrom. We had no choice but to swim through the thick vegetation surrounding the shore. Fortunately for us, the caiman, eels and anaconda were all preoccupied elsewhere (probably hiding from the storm), and we made it to shore without incident. After the storm abated we made our way back to the pier where we had taken the cayuco. Carmela and about ten other villagers were there – when they saw us they looked shocked, like they were seeing ghosts – they all thought we must have drowned in the storm!

Our work on R. variabilis yielded some interesting results, and I was able to combine our field observations with laboratory analyses of genetic relationships (done in Bill Amos’ lab at the University of Cambridge) to provide evidence that these frogs have a promiscuous mating system and that cannibalism (of small tadpoles by large tadpoles) occurs between both relatives and non-relatives (Summers & Amos 1997).

I returned to Limoncocha years later after starting as an assistant professor at ECU. My assistant and I again lived in town, and hiked into the forest to work everyday. We worked in a beautiful, uninhabited part of the forest near the Napo River, several miles from the village of Limoncocha. In spite of some episodes with flooding, our work (on the breeding ecology in Ranitomeya variabilis) went well. However, one day my assistant and I were working about a quarter of a mile apart, I heard a loud scream. I ran back, and found my assistant trembling in shock, but otherwise unharmed. When I asked her what had happened she said she had been approached by a man of indigenous appearance dressed only in a loincloth, with a small feather headress on his brow, carrying a long (six foot) wooden spear (in the manner of the Waorani). After approaching her, he pointed toward her belt pouch and said “plata” (the spanish word for sliver, which is slang for “money”). Not knowing what else to do, my assistant removed her belt pack and gave it to the man, upon which he abruptly turned and disappeared into the forest. Now, most of the things in the belt pouch (tweezers, small scissors, mini-flashlight, etc.) were easily replaceable (ironically, there was no money – we don’t need it in the field). There was, however, one irreplaceable item – my assistant’s field notebook, containing several weeks worth of data that we had failed to transcribe at that point (an important lesson for field biologists here – transcribe your data every night!). We were both mortified at losing this priceless item, and went to talk to the local police in Limoncocha. They came to the site with us to look around, but were unable to offer much in the way of practical help. After searching all day, we were sitting in a small clearing were we kept a few stools to sit on while eating lunch during the middle of the day. We also kept a small garbage bag for any wrappers, etc., from lunch items, that we would carry back to Limoncocha every few days. On a whim, we looked into the garbage bag, and there, nestled among the wrappers, was the field notebook! This fellow had the entire forest in which to dispose of the field notebook, but instead he found our little garbage bag in the middle of the forest and decided that was the most appropriate place for that particular piece of garbage! Whether this was a comment to us concerning his opinion of the value of our research, or simple fastidiousness, we shall never know… Of course, it is highly unlikely that this fellow was actually Waorani. If we actually been acosted by a Waorani raiding party, I would probably be dead, and my assistant would be pounding yucca root somewhere deep in the rainforest… Most likely, this was a local Quechua villager who had heard about the gringos working in the forest, and decided that dressing up like a Waorani warrior and demanding money from us would be a profitable enterprise. Years later, my wife, Sue McRae and I did encounter a hunting party of Waorani.

We traveled to the Yasuni Reserve to see relatively pristine rainforest, spending several weeks at the Yasuni field station. The forest around the reserve is a remarkable place, with an incredible diversity of birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians and insects. Exotic wildlife on the reserve includes river dolphins, manatees, giant otters, hoatzins, anacondas, black caiman, scarlet macaws, harpy eagles, jaguars, pygmy marmosets, among many other iconic species.

The reserve is particularly rich in primate species, and a number of primate research groups have worked in the area. One complication, however, is that the region is part of the traditional hunting grounds of the Waorani, and monkeys are a sought after item for the typical Waorani menu. Hence, some research groups have actually tried to pay the local Waorani not to hunt the primate groups they are trying to study! As you might expect, this didn’t work out so well – as you might imagine, the Waorani were happy to take the payments, but foregoing their traditional hunting practices is easier said then done, and the researchers frequently found that some of their focal research animals had suddenly gone missing. This caused some primate researchers to move to other areas, outside of the traditional Waorani hunting grounds. Sue and I were with a group of researchers when we ran into a Waorani hunting party one day – they were indeed a formidable looking group of men – small in stature but incredibly fit and strong looking.

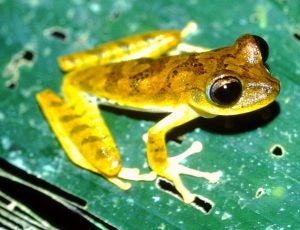

Limoncocha and the nearby Yasuni Reserve are in one of the most biodiverse areas in the world, especially for amphibians. While my research focus there was on the ecology and behavior of Ranitomeya variabilis, I could not help but be fascinated by all the other frogs surrounding me, and would often go out at night to see what could be seen.

Unfortunately, even in those days, the oil companies were making steady progress into the Yasuni Reserve, which was having a huge impact on the wildlife as well as the Waorani. For example, one night we went to see the “burn-off” area, a place where the oil company was burning off excess natural gas that was coming from the oil fields they were drilling underground. This was a massive pipe rising into the air, with flames shooting out of it, creating a blazing beacon that attracted forest insects from miles around. The ground around the area was littered with the partially burned corpses of insects that were flying too close to the inferno and being immolated or simply succumbing to the extreme heat. The carnage included amazing species such as the gigantic hercules beetle seen in this photo.

One night in Yasuni Sue and I were walking in forest when we heard a loud, strange “knock knock” call coming from the trees. After walking around trying to locate it, I finally found the tree that it seemed to be coming from. Unfortunately, my headlamp went out after I had climbed up about ten feet, so I had to continue without light(!) I came to the spot where the call seemed to be coming from, and could vaguely see a treehole in the dim moonlight. I reached into the hole, and after searching around abit, grabbed what felt like a large frog and pulled it out. It turned out to be a Nyctimantus rugiceps, a beautiful hylid frog. The males of this species call from treeholes, where they take care of the eggs the lucky ones get from females. We took it back to the station to take pictures, then brought it back to the tree to release it the next day.

Another amazing treefrog we saw at Yasuni was Dendrosophus marmorata. One night it rained intensely and a breeding congregation of this species appeared right next to one of the station buildings. We had a great time taking photos of these gorgeous frogs.

I saw many other species of frogs in Amazonian Ecuador, some of which are described below.