Tropical Terrestrial Ecology Course

The rainforests of Panama are home to one of the most diverse collections of plants and animals on the planet, and have attracted scientists and natural historians for many decades. After the completion of the Panama Canal, the Smithsonian Institution began to set up a series of research centers in Panama, centered on Barro Colorado Island (an island in Lake Gatun, a lake created by the construction of the canal). This was the origin of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, which has now expanded to include multiple tropical research centers across Panama and across the globe (STRI).

I began my long association with STRI when I received a fellowship to do research on there in 1985. I did much of my doctoral thesis research on poison frogs in Panama, as well as postdoctoral research, with the support of STRI and a number of staff and visiting scientists. Later, as a postdoctoral researcher at Cambridge University, I met Susan McRae (a graduate student at Cambridge at the time), who would later become my life partner. Sue received a postdoctoral fellowship at STRI in 1999 to work on reproductive strategies in moorhens, and worked in Panama for several years. I was an assistant professor at East Carolina University in the states at this time, and came to Panama at various times to continue his research there. Beginning in 2007, Sue and I began leading a field course in Panama, and we took our daughters, Anita (born 2001) and Veronica (born 2004) every time we went for the next six years. The course was based in Gamboa, a small town on the Panama Canal.

Our course typically consists of 6-12 undergraduates, most of whom have never been to the tropics before. We fly down to Panama City, and take a van or bus (kindly provided by STRI) to Gamboa. Gamboa is about halfway between the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean, originally built to house the workers of the Canal Dredging Division, whose efforts keep the canal from filling up with silt and halting the flow of boat traffic. Boat traffic through the canal is a major economic boon for Panama, with large cargo trips paying over a hundred thousand dollars just to make the transit.

Many of the areas surrounding Gamboa (adjacent to the canal) provide critical watershed protection (preventing erosion), and hence have been designated as protected natural areas. This made the area a paradise for tropical biology, and many STRI scientists settled in Gamboa so as to be in easy proximity to the flora and fauna of the rainforest.

Over the years, STRI and STRI staff have obtained various forms of housing in Gamboa, including a small apartment complex, and a former schoolhouse which is used to provide lodging and classrooms for students visiting for field courses.

The course centers on tropical ecology and evolution, with a strong focus on local fauna, especially avifauna (Susan’s speciality) and herpetofauna.

A Stroll Through Gamboa

We typically begin the course with hikes through the forest in and around gamboa, which can reveal a plethora of wildlife. We might see a titi monkey, a trogon or even a basilisk and in the trees.

Titi monkeys are small callitrichid primates that travel in small family groups. They are known for having extensive paternal care, and in some species show a polyandrous mating system in which two males cooperate to care for the offspring of one female. The groups of Titi monkeys living in Gamboa are remarkably tame, having been offered backyard food by local residents for many years. They are very curious, and will approach quite close to humans to investigate.

Another commonly seen Gamboa resident is the nine-banded armadillo. These small armored mammals seem to have poor vision, but a keen sense of smell. They snuffle through the undergrowth and root into the soil, apparently search for tasty morsels like earthworms or beetle larvae. They seem to be largely oblivious of humans, and will come right up and snuffle you if you happen to be in their pathway.

A common denizen of the underbrush in Gamboa is the agouti. This large rodent can often be seen seeking out seed pods that it can gnaw open with its hardy, chisel-like teeth. This mammal plays an important role in seed dispersal – it buries multiple seeds away from the parent tree, but may forget their location or simply be depredated before recovering the seed (Agouti seed dispersal). Agoutis are also important prey for many different predators in the rainforest.

A Walk Along the Chagres River

A Walk along the Chagres River is always exciting, with many reptiles and birds out and about, often in places where they can be easily observed. The riverbanks are popular with basilisk lizards. Basilisks are also known as “Jesus Lizards” because they can “walk on water”. Actually, when they are disturbed, they will run on water (running basilisk), using their long, splayed toes to distribute their body weight and avoid sinking below the surface (at least until they are well away from the danger).

Another common sight is the iguana. These lizards start out small, cute and very green, but then get really big. Despite their large size, they are quite at home in the canopy, and can often be seen high up in the trees. They are somewhat wary of humans, which makes sense, because they are a common item on the menu for many rural populations in Central America.

Crocodiles and caimans are not uncommon in the canal. While caimans generally steer clear of humans in Central America, Crocodiles are not so deferential. When I first started visiting BCI in the 1980’s, it was not uncommon for researchers on Barro Colorado Island to go for a midnight swim in the canal (Lake Gatun). However, a few crocodile attacks on swimmers put a stop to that, and generally speaking it is wise not to swim in the Canal or the Chagres River.

The Charges and the canal are also home to many waterbirds, including Jacanas. These birds are known for their huge splayed toes, which help then distribute their weight on the lilypads they walk about on on the water’s surface. They are also well-known for their behavior, providing a rare example of “sex role reversal”, in which males carry out all the parental care and females fight for control of territories on the river and the parental males they contain. Successful females will monopolize the parental services of multiple males, while the losers are relegated to “floater” status, hanging around the outskirts of the desirable territories and hoping one of the dominant females dies so they can move in (Jacana video).

Another waterbird seen frequently on the river is the moorhen. These birds are distributed across the world and exhibit a number of fascinating behaviors, including intra-specific brood parasitism and cooperative breeding. Sue has studied these behaviors in this species in Panama as well as in Europe and Africa.

The shores of the Chagres are also a good place to spot the world’s largest rodent, the Capybara. This giant rodent loves the water, and large family groups consisting of a dominant male, several adult females, and various subadults and juveniles are a common sight.

The Frogs of Kent’s Marsh

Kent’s Marsh is a field on the outskirts of Gamboa that fills up with ankle to knee-deep water with the advent of the heavy rains in the rainy season (starting around June). It is named after Kentwood Wells, a professor of evolutionary biology at the University of Connecticut and one of the world’s leading experts on amphibian behavior (Tribute to Kent Wells). Dr. Wells spent many nights in the marsh studying the breeding behaviors of a variety of frogs, as did many of his students after him. The number of different species found calling in this swampy field is remarkable, producing a cacophony of sound that one will not soon forget (Tropical Frog Chorus). Frogs of many kinds can also be found in other parts of Gamboa, such as the streams emptying in to the Chagres, and the ponds on the northeastern side of town (see below). We typically spend at least one evening exploring Kent’s Marsh and marveling at the diversity of species found there.

One of the most commonly seen tree frogs in the marsh is Dendrosophus ebracattus, the “hourglass” treefrog (so named because of the markings on its dorsum). The frog creates a cacophony of sound as males vie with each other to present the loudest, most distinctive acoustic stimulus to any prospective mates that might be visiting the marsh that evening. This species has been the subject of a huge amount of research on things like acoustic behavior and reproductive mode (Justin Touchon: Frog Whisperer).

Another commonly seen frog is Scinax boulengeri. Frogs of this genus contribute their own unique sounds to the chorus. Frogs in this genus have been model organisms for studies of the physiology of calling behavior. Calling is a costly, demanding activity as a number of studies have demonstrated. Different species of Scinax have different strategies – some call intensely but only for a few nights, whereas others persist in the chorus for much longer periods, but call at lower rates to save energy (calling tradeoffs).

Smilisca phaeota, the masked treefrog, is a large, handsome tree frog that for some reason likes to hang around man-made structures (hence you may occasionally find yourself taking a shower with one of these frogs). They have an unusual ability to change color facultatively from yellow to green. This may allow them to more effectively camouflage themselves against different backgrounds. Their call is a startlingly loud “AWRK!” that can make you jump if you are not expecting it! These frogs breed opportunistically after heavy rains in the rainy season.

The Tungara frog is a small, unobtrusive looking little frog that has probably been the subject of more research in Gamboa than any other species (Tungaras and Sexual Selection) (Michael Ryan Interview). They even use robotic frogs to carry out experiments on these frogs! (Robotic Frog Video). Males give a complex call that attracts females, but also attracts predatory bats that would like to eat them. As you can see from the picture mosquitoes also like to feed on these frogs. They are abundant and love to breed in roadside ditches. Pairs will stir up a mass of frothy foam by beating their hind legs together – this foam provides some protection for the eggs.

One sound that rises above the rest of the chorus in the marsh is a loud “Whoop, Whoop!”. This is the call of Leptodactylus savagei, Savage’s thin-toed frog (named after the famous tropical herpetologist, Jay Savage (BioOne: Savage)). This gigantic frog is a voracious predator on other frog species, and woe betide any hapless small tree frog that comes too close to one of these frogs. As you can see from the photo, their eyes tend to glow red in the light from camera flashes, giving them a rather demonic aspect. Given their voracious habits, this seems appropriate.

A tiny frog that can sometimes be found in the marsh (and other places) is the microhylid (narrow mouthed toad), Chiasmocleis panamensis. This little guy has a very pointy snout, characteristic of this group of frogs (probably useful for burrowing). They are usually out after heavy rains, calling with a high-pitched trill.

Another frog that one may be lucky enough to see in this area is Leptodactylus bolivianus. This species is unusual in that females actually guard their brood of tadpoles, which form a little ball of siblings around the mother (parental care is uncommon in frogs, but is much more common in tropical than temperate species. This video shows an irate momma frog repeatedly attacking a human pretending to be a tadpole predator (L. insularum video)!

Hiking the Plantation Trail

The Plantation Trail passes through beautiful rainforest as it meanders up a hillside from the highway.

Walking through the forest, it is not uncommon to hear the rough, throaty calls of howler monkey troops announcing their territories to other troops. Sometimes you may be lucky enough to encounter a troop foraging low in the canopy. Howlers tend to be slow moving (probably due to their folivorous diet), and so it is sometimes possible to keep them in view for a long time. They are also quite territorial – and will respond aggressively if other troops try to encroach upon their territory.

In the avian realm, a huge diversity of birds can be seen flitting about in the canopy along this trail. One of our favorites is the Trogon. These stout yet beautiful birds often sit calmly while passing ecotourists ooh and aah at their gorgeous plumage. They are related to the even more spectacular quetzal (see Fortuna page). In spite of their beauty, they are often difficult to see, because they tend to remain very still. This may be a strategy to avoid predation, as it is harder for predators to detect animals that are not moving.

Frogs are often seen on this trail as well, even in the daytime. Rain frogs (also known as robber frogs) in the genus Pristimantis and Craugastor are often seen in the leaf litter along the sides of the trail, although they can be hard to spot because they are well-camouflaged.

Speaking of well-camouflaged, another small anuran commonly seen in the daytime is Rhinella alata. This small toad comes in a bewildering variety of different shades of brown and beige, with different (yet all leaf-like) patterns (see photo montage below).

Recent work (R. alata camouflage) indicates that this kind of patterning serves as a form of “disruptive coloration”, interfering with the ability of predators to identify the outline of the toads in the leaf litter. Over the years, many (including us!) have speculated that the diversity of different patterns in these toads results from selection (imposed by predation) to look different than other nearby toads, so that predators are less able to form a single search image that allows them to distinguish a toad from a leaf. To my knowledge, this idea remains to be rigorously tested.

After a long hike on the Plantation Trail, it is wonderful to take a dip in the pool at the base of Charco Falls.

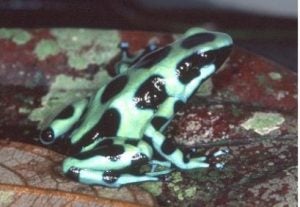

The forest near the falls is home to the green and black poison frog, Dendrobates auratus. This species shows the stunning bright coloration characteristic of this family of poison frogs (Dendrobatidae). These frogs are highly toxic (poison frog video), giving them the freedom to move about in the open during the daytime, in contrast to the nocturnal habits of most frogs. This species also has complex parental care, carried out by the males, who transport tadpoles on their back to small pools of water in treeholes (phytotelmata).

Journey to the Canopy (Tower)

There are several canopy towers dedicated to birdwatching near Gamboa, but we typically go to the one off of Pipeline Road (Canopy Tower Videos). The entrance to the trail to the tower is an absolute hummingbird paradise. There are many hummingbird feeders deployed and the local hummingbirds have learned that this is the place to be. These photos give just a small taste of the incredible diversity of these gorgeous little birds at this place.

Beyond the hummingbird paradise, there are many other fascinating birds to be seen along the trail to the canopy tower. One of my favorites is the ant shrike, with its striking plumage and bold behavior (barred antshrikes).

This is also a good place to see the elusive Rufous Ground Cuckoo, although I have not seen one here myself (ground cuckoo video). The trail to the tower also offers some good frogging – right near the base of the tower is an excellent place to see several species of rocket frogs, especially Allobates talamancae (left) and Silverstoneia flotator. These frogs are closely related to the Neotropical poison frogs (like the green and black poison frog – see above).

These frogs share the diurnal habits of the poison frogs but not their toxicity or bright coloration. They also share the parental care habits that poison frogs are famous for, and it is not uncommon to see males with their backs covered with tadpoles, carrying them to a nearby stream, as in the photo at left.

Climbing the tower to the top reveals an absolutely stunning 360 degree view of the canopy and the hills of central Panama.

The canopy tower is a great place to observe hard to see species, such as the toucan, the aracari, and many others. Small fruit eaters are very abundant and can be seen from the canopy tower, including beautiful species such as euphonias and tanagers. And that is only the beginning! Careful searching and observation with a pair of binoculars will reward one with sights of a huge variety of avian life, from large birds of prey, to parrots and macaws, to chachalacas and guans, and so on…

The Frog Pond: Home of the Red-Eyed Treefrog

On the northeast side of Gamboa there is an artificial frog pond that attracts breeding populations of a number of species, most notably the red-eyed tree frog (Agalychnis callidryas), which is an icon of the Panamanian rainforest. This species, well known for its bug-eyed beauty, has also been the subject of much research on its mating behaviors and breeding habits by Dr. Karen Warkentin and her students and colleagues (red-eyed treefrog video), and particularly on hatching plasticity in response to the threat of predation. This frog attaches its clutches to leaves overhanging water. When predators, like cat-eyed snakes, come around and attack the clutch, the tadpoles (after a certain age), will actually accelerate hatching, so that they hatch and drop into the water before becoming the snake’s next meal(!). This is an amazing phenomenon, and can been seen before one’s very eyes on film (Red-eyed treefro tads 1)(Red-eye treefrog tads 2). They can also do this in response to wasp attacks (Red-eyed treefrog tads and wasps) and even fungus attacks!

A hungry cat-eyed snake on the lookout for some tasty Agalychnis eggs or tadpoles.

Another frog that is commonly seen near the frog pond is the gladiator frog, Hypsiboas rosenbergi. This large, handsome tree frog is named “gladiator” because the males of the species will engage in sometimes lethal fights using long, extremely sharp prepollical spines. Males use small basins they construct to raise their eggs and tadpoles, and will defend these basins vigorously against other males that try to usurp their pool. This species was studied extensively by my advisor at the University of Michigan, Dr. Arnold Kluge, back in the 1970s (Kluge UMMZ).

Birding on Pipeline Road

Pipeline road was built to monitor an oil pipeline running from Gamboa to the Caribbean, but it passes through some pristine rainforest and is used by many STRI researchers to study a diversity of tropical plants and animals. Panama has an amazing diversity of avian species, and Pipeline Road is one of the best places to see them! (Birds of Panama).

A bewildering diversity of species live in the forest along either side of this road, manakins to currasows.

Birding on Pipeline Road (photo by Susan McRae)

The Rio Frijoles is a small, clear river that runs through pristine rainforest down to the Panama Canal. Walking along or in the river provides excellent opportunities to see a number of birds species, as well as reptiles such as basilisks and iguanas.

Pipeline Road is also an excellent place to see tropical insects of many kinds, such as the beautiful butterfly above. An astounding variety of insect life inhabits the rainforest, and it is not unusual to stumble upon bizarre examples, such as this giant caterpillar. Another giant insect that can be seen on recently fallen fig trees is the harlequin beetle, which is kind of the Airbus of the rainforest (Harlequin beetle video).

One never knows what kind of bizarre insects one will encounter in the rainforest, but here are a few examples. These two homopteran leaf-hoppers seemed to be engaged in some kind of display, but it is hard to say for sure.

Caterpillars come in many forms in the forest, but usually have some kind of protection, such as toxins or spines (or both, in this case)!

Hymenopterans (ants, bees and wasps) are ubiquitous in the rainforest, and you can even run into an entire wasp nest hanging under a leaf! However, this is not recommended…

This photo shows and ant tending to its “herd” – a group of homopterans. These little guys suck sap from the plant, and convert it into a sugary secretion which is then offered to the ants. The ants provide protection to their little “sheep” in exchange for access to this rich resource – they will defend them against all comers, including formidable flying foes like wasps.

The beautiful butterfly is a morpho, which can frequently be seen flying in an erratic fashion (apparently to deter predators) through the forest.

Some butterflies have what are called “eyespots”, which are hidden when the butterfly has its wings closed together (typical when perched), but when disturbed can open its wings to reveal these startling eye-like spots, presumably scaring the bejesus out of any would-be predator long enough for the butterfly to fly away.

The fellow below looks like an ant, but looks can be deceiving! This creature is not even an insect, but a spider (arachnid), pretending to be an ant. Given their notorious distastefullness, and generally nasty, aggressive disposition, most predators don’t mess with ants, and so everybody wants to look like them!

On BCI, they actually put flags near the nests of these ants, so that unwary hikers will not step on the nest, causing the ants to swarm aggressively against the intruder.

Other species just pretend to be something distasteful or unappetizing, like this caterpillar pretending to be a pile of bird poop(!). The resemblance is actually quite remarkable.

One might find an insect that, while it doesn’t look like poop, really loves to play with poop – and not its own, either. The famous dung beetle can rapidly locate freshly deposited poop, and promptly roll a ball of it away to feed it’s larvae. Males of this species will vie to control the burrows that females set up and fortify (with poop) for their offspring. Remarkably, as documented by Douglas Emlen (dung beetle sexual selection), these beetles have two alternative tactics, depending on whether they are big or small: big beetles will fight to control access to the tunnel of a female, whereas little males will try to make a tunnel connect to that of the female, so they can sneak in and mate with her, without attracting the attention of the big guarding male (against whom they would have no chance in a fight). In the study of alternative strategies, this is a classic example of the evolution of conditional alternative tactics, controlled by environmental factors (dung beetle conditiion-dependent tactics).

Night on Pipeline Road: Glass Frogs on the Rio Frijoles

We return to the Frijoles at night with my former student, Jesse Delia, who has been working on glass frogs on Pipeline Road. These frogs are aptly named, as their tissues are so transparent you can actually see their internal organs! (See-through frog video)(See-through frog photo). Jesse studies their amazing mating parental behavior, which is both complex (Glass Frogs Mating) and vigorous (Glass Frog Parental Protection).

Jesse has published extensively on the behavior of these remarkable frogs (Parental care evolution in glass frogs).

The oddly named “Grainy Cochran Frog” (Cochranella granulosa) is a gorgeous glass frog that can be seen fairly easily on the leaves of plants overhanging the Rio Frijoles at night. Combined with translucent skin, this species is suffused with a blueish tinge, and has a multitude of brightly colored spots, making it look like a work of art from some pointillist impressionist painter.

There are plenty of insects and arachnids to be seen on the Frijoles at night as well. Some, like this daddy long-legs are also excellent parents. Many species of daddy long-legs have intensive male parental care (typically of the egg stage).

Night-time on Pipeline Road is also a good time to spot some nocturnal mammals. For example, night monkeys, or owl monkeys (genus Aotus) can some times be spotted moving through the foliage of the trees with a good headlamp. These monkeys are very shy, but will sometimes approach humans to get a better look. They have an unusual form of parental care with parallels to some glass frogs (and daddy long-legs) – the male does most of the parental care (owl monkey video).

Another mammal you might see clambering through branches in the trees is the kinkajou. This fellow looks like a strange monkey, but is actually related to raccoons and coati mundis (see below). They are frugivores, and spend their nights looking for and devouring the many tropical fruits on offer in the canopy of the rainforest (Kinkajou video). The best way to spot them up there is with a strong spotlight, with which you may see the baleful stare of their large eyes reflected back at you as you shine the light up into the branches of the trees.

Pipeline Road is also one of the best places in Panama to see the famous big cat, the jaguar. These large cats are shy and elusive, but are sometimes seen crossing the road or slipping out of sight in the forest.

A Day on Barro Colorado Island

Barro Colorado Island was formed when the canal was filled, forming Lake Gatun and a number of islands. This island has become a center for STRI’s research efforts, and researchers from around the world have come to the island to investigate many facets of tropical ecology and evolution (BCI STRI Video).

I have been visiting the island since the mid-1980s, when the old facilities at the top of the hill were the only ones available. Since then, new, modern facilities have been built closer to the lake, and this is where most researchers are housed these days. The old cafeteria building now houses exhibits on STRI research, but back in the day it was the place to hang out when not doing research.

The smell of food would attract a variety of visitors, including non-human visitors. For example, spider monkeys are one of the bolder primates on the island, and would often come round the cafeteria looking for handouts, or, if the opportunity arose, any food that was not carefully guarded and could be grabbed!

Another frequent “hopeful visitor” was Bertha the tapir. Tapirs are the largest mammals on BCI, yet are normally rarely seen as they are shy and elusive. Bertha, however, learned that the cafeteria was a good place to get a snack, and could often be seen hanging about in the hope of getting a handout. The cooks were often nice to Bertha and would give her treats.

BCI is an excellent place to observe primates. In addition to the spider monkeys mentioned previously, there are also capuchins, howlers, night monkeys and marmosets. The howlers and capuchins, in particular, have been the subject of long-term research by primatologists, such as Katy Milton (Milton Website) and Meg Crofoot (Crofoot video). Capuchins are fun

to watch because they are so curious and active (Capuchin video). They can, however, get annoyed with observers trying to follow them. I remember one day trying to follow a troupe climbing through the trees when a male turned and looked down at me. I was so busy trying to get a picture I didn’t notice that he was actually coming down towards me – he came within 20 feet and started screaming and throwing things, at which point I realized that he was not just being curious – he wanted me the heck out of there!

The social lives of capuchins are fascinating, and have also been studied extensively in Costa Rica. A friend of mine from graduate school at the University of Michigan, Suzanne Perry, has maintained a long-term study of capuchins in Lomas Barbudal National Park that has revealed many aspects of capuchin social behavior (Lomas Barbudal)(How to be a Capuchin).

Another commonly seen mammal on BCI is the coati mundi (Coati foraging). These animals are related to raccoons, but have a more social nature. Females (and dependent offspring), in particular, live in large groups, whereas males are more solitary. They have a rather playful and mischievous nature, and can often be found getting into one sort of trouble or another.

Big cats like jaguars don’t remain on BCI (although they may visit), but resident cats don’t get any bigger than the ocelot. Nevertheless, ocelots are beautiful cats (and they do have big feet!). Of course, these cats are very elusive and hard to see. Your chances of seeing one during the day are virtually nil, and and not much better at night. However, researchers on BCI have been tracking these cats closely using radio-tracking collars and highly accurate radio-tracking technology enabled by the construction of large broadcasting towers and an automated radio-telemetry system (tracking ocelots and agoutis).

After a long hike through the forest, we arrive at the giant buttresses of the big tree on the island. Unfortunately, this giant was felled by a huge storm a few years ago, although this does give students the opportunity to observe a crucial phase of rainforest succession first hand.

Nightwings: Going Batty

Upon first entering the Gamboa schoolhouse that STRI uses as a dorm, one used to be greeted by a small party of beautiful little bats, just hanging out (some with baby bats clinging to their bellies). STRI has a long tradition of supporting research on bats, and it is not uncommon to see researchers catching bats at night in and around Gamboa.

The diversity of bats in this region is astounding, and they have a huge range of life histories. Many bats are insectivorous, but there are also bats that eat fruit, drink nectar, and even catch fish! (fishing bats). Walking through the forest one can even find bats hiding under leaves – the tent making bats modify the leaves of large-leaved plants to form a tent-like structure where they can shelter (tent-making bats).

There are even bats that specialize in hunting frogs. Dr. Rachel Page has been studying this species for many years, using experiments to explore how individuals learn to locate the frogs using acoustic cues in the complex physical and auditory environment of the rainforest (Unlucky Tungara frogs)(Bats and noise). Dr. Page has been studying this species for many years, using experiments to explore how individuals learn to locate the frogs using acoustic cues in the complex physical and auditory environment of the rainforest (Rachel Page video).

Dr. Page and her associates have been able to train these bats to respond to frog call playbacks from speakers in a special platform covered with leaf litter, as seen in this photo. Fortunately for frogophiles, she has been able to switch the reward for locating the call from frogs to fish! They can even train them to home in on cell phone rings (bat learning)!

The bat that probably inspires the most fear in people is the vampire bat. This bat is famous for drinking the blood of sleeping mammals. It has a suite of adaptations that enable it to feast on their blood undetected (vampire bat adaptations). The increase in the availability of large mammals with the advent of domesticated animals like cows and pigs provided a vastly increased supply of blood for vampire bats, leading to population increases in some areas. This has become a source of conflict in some regions, as vampire bats can carry the deadly disease rabies, and can pass it on to both domestic animals and humans. At the same time, these bats have remarkable social lives, being one of the only non-human animals demonstrated to show reciprocity (vampire bat video)(vampire bat reciprocity review).

Heliconius Heaven

Heliconius butterfly

Heliconius Research Facility Gamboa

Heliconius Research Facility Gamboa

The Heliconius facility in Gamboa houses breeding and experimental cages for many species of Heliconius butterflies. These beautiful butterflies have been the subject of much research on aposematism and mimicry (Heliconius video). Researchers have found that hybridization and the resulting gene exchange can contribute to the evolution of mimicry (hybridization and mimicry). These butterflies have also been models for the study of speciation (Heliconius and speciation), and for how mimicry can drive the process of speciation (mimicry and speciation). Genomic studies have begun to unravel the genetic mechanisms that control the color pattern variation and convergence that underlies mimicry in these butterflies (Heliconius mimicry genes)(mimicry genes 2).

The Heliconius Research Facility provides facilities for many different kinds of research on these remarkable insects, from mate choice trials to crosses between different morphs for genetic analyses, and from experiments on feeding behavior and host plant choice to the nighttime roosting behavior of groups of individuals.

In spite of their beauty and fascinating biology, Heliconius butterflies are not the only insects that have attracted lots of attention from scientists in Gamboa. For example, a veritable army of scientists have been studying the biology of the leaf cutter ants (leaf cutter video 1). These ants developed agriculture about 50 million years before we humans did, and different species have been busy refining it in many different ways (Sunshine Van Bael interview). These ants have evolved a mutualism with specific types of fungi, for which they provide the raw material for the fungi to grow (leaves). In turn, the fungi convert the indigestible cellulose of the leaves into edible hyphae that the ants can feed to their offspring. The ants have even evolved to use specific bacteria to produce pharmaceuticals that can be used to combat other species of fungi that threaten their mutualist fungi gardens. The study of these ants may yield new pharmaceuticals useful to humans, and may reveal new methods to convert plant material into biofuels (leaf cutter video 2) (leaf cutter video 3).

Another focus of scientific attention has been the mutualism between fig wasps and their host fig trees. This is another example of an ancient mutualism, this time between tiny wasps and their gigantic host. Fig wasps are entirely dependent on the figs provided by their hosts to provide resources and shelter to their offspring, and in turn the fig wasps provide pollination services to the fig tree (Fig wasp video). While the fig – fig-wasp mutualism has endured for a long time (>65 million years!), this does not mean that the relationship is entirely cooperative, as the fig may sometimes cheat the wasps, and vice versa (Figs vs. fig-wasps). STRI scientists Allen Herre and Charlotte Jander have been studying this mutualism in Panama for many years, and have identified a variety of mechanisms whereby mutualistic cooperation is enforced and cheating is discouraged (fig-wasp cheating 1)(fig-wasp cheating 2).

Frog Rescue Mission

Panama is home to an incredible diversity of frog species (Panama frog exhibit). The frog rescue center in Gamboa is dedicated to saving threatened species that are in danger of extinction (amphibian rescue site). Like a number of other regions, Central and South America has been hit with a devastating plague that has decimated frog population in many localities, especially those at higher altitudes. The chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis) is a novel pathogen that swept through Central America from north to south, and simultaneously swept through populations in South America, especially in the Andean regions and other montane areas. Researchers, like Dr. Roberto Ibanez, working with STRI and other international conservation organizations have been attempting to rescue frog species endangered by this catastrophic pathogen (disappearing frogs), while also studying the pathogen and its effects to try to find long-term solutions to the epidemic (Amphibian rescue video 1) (Amphibian rescue video 2). Recently, researchers have found that some highland populations may be starting to rebound from the devastation caused by the chytrid pathogen, possibly by the evolution of resistance, although the cause remains speculative (Chytrid recovery article).

Beyond their natural, intrinsic beauty, frogs are integral parts of rainforest ecosystems. Also, many of these endangered species have toxins in their skin that may provide a cornucopia of new chemicals. In turn, these chemicals may provide the basis for new medicines to cure intractable diseases (frog toxins and medicine), as well as new tools for biochemical investigations of key aspects of cell physiology, such as ion channel regulation.

A Visit to a Wounaan Village in Gamboa

The Wounaan and Embera tribes are indigenous to the Darien region in Eastern Panama and into Colombia (the Darien Gap), but small groups of individuals from these tribes were brought to Gamboa by the US military to train their soldiers in jungle survival. These groups eventually established small villages which have remained to this day.

The journey along the banks of the Chagres river to the village is filled with wildlife. In addition to the jacanas and moorhens mentioned above, other waterbirds like purple gallinules and whistling ducks are abundant and easily observed. The ducks seem to really enjoy hanging out in trees – perhaps it keeps them out of reach of the caimans and crocodiles.

The village itself is built in the traditional style, with a the floor built well above the ground on posts. Protection from the rain is provided by palm leaf thatching, but the sides of the structure is open, allowing the breeze to blow through and cool the occupants during the hot days and warm nights.

The tour includes traditional music and dance performed by the residents.

After our tour, we all get tattoos made from a dye from a local plant (henna) – the villagers will paint any design you desire, from traditional geometric designs, to animals including snakes, birds or big cats.

Tattoos!

Naos Peninsula

The Naos Peninsula, on the Pacific Ocean end of the Panama Canal, is home to a small patch of forest which is one of the best places to see sloths in Panama. The small size of the patch of forest, and the relatively open canopy, makes these slow but beautiful animals hard to miss.

Sloths have an ultra-slow metabolism that allows them to survive on an extremely low calorie diet (leaves). They also spend inordinate amounts of time sleeping (Sleepy sloths). Sloths have a curious habit of descending to the base of their tree to defecate – some think this may serve to avoid olfactory cues that predators might use to locate sloths in canopy, but this is speculative (Sloth descending).

Naos also houses an excellent STRI exhibit on marine life, and provides one of the best places to see crab behavior in the wild. Before retiring, Dr. John Christy gave fascinating lectures to our course each year.

These were made all the more intriguing because the fiddler crabs would carry out their typical display behaviors right behind Dr. Christy as he gave his lectures on the beach (fiddler crabs)! He would also guide the students in very hands on sessions of behavioral observation, giving the students an invaluable introduction to the subtle art of studying the behavior of wild animals in the field. Dr. Christy has studied these crabs for many decades, and gleaned many important insights into the principles of animal behavior from his studies (crab claws). For example, Dr. Christy’s research has revealed that these crabs provide a clear cut example of “sensory exploitation”, in which males are able to tap into specific features of the females’ evolved sensory system to maximize their chances of attracting a female to their burrow (John Christy videos).